“How can something that you love so much become so evil?”

Mollie Perella investigates the powder hungry who are putting life in peril to ski the perfect run and talks to experts in the field about what goes on beneath the surface…

Skiier, sports model and general snow sports poster girl Amie Engerbretson describes the time she was caught in an avalanche as “a lot like being pummelled by a wave; the water just has control over your body and you can’t really fight it”.

As backcountry skiing is quickly becoming the fastest growing sector of the ski industry, with MEC reporting that sales in back country gear increased by 40% in the 2013 season, it’s time to start thinking more about how to stay safe on the mountains. With growing technological advancements and more knowledge in the field, we know more about avalanches than ever before, meaning we can prepare better for the worst case scenarios.

Martin Papillon, an avalanche rescuer from Banff describes skiing powder as “a different feeling. The speed and the adrenaline rush felt all the way through it at the same time as the view around you and the mountains and being with friends…It’s not comparable to anything else I don’t think.’’

But that powder you’re chasing? It’s one of the main reasons you are at risk on the slopes.

Blair Fyffe is the man in the know. With years of backcountry experience and multiple snow qualifications under his belt, he talks us through the science of the stuff we love. Scientific research shows that avalanches are triggered by the failure of a layer within the snowpack, which is too weak to support the overlying layers, causing great slabs of snow to break loose and slide off down the mountain. These faults occur in weak layers, which unfortunately includes fresh powder.

Avalanches gain speed and grow in mass and volume as they entrain more snow. When the avalanche runs out of energy, it stops and settles like concrete, leaving anything stuck inside it with a very small chance of getting out. Amie recalls being buried for three minutes: “I realised I was essentially in cement. I couldn’t move a muscle.”

Blair explains that there are two types of avalanches that can occur, both with the ability to carry you for miles.

A loose snow avalanche begins from a single point on a slope, then gathers cohesion less snow from the surface of the snowpack as it descends. These avalanches often occur in an inverted V shape on the slope. They are not as dangerous as slabs, but Blair explains they still have the ability to bury people caught up inside one. They fracture beneath you as you cross the slope, instead of above you.

Slab avalanches consist of snow from a single storm, or from multiple layers of snow from several storms. They are very powerful and cause the most fatalities, this is what Amie was caught in; the Utah Avalanche report for her incident said it was a ‘soft slab’.

-

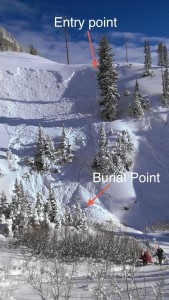

This diagram shows where the Avalanche point occurred and how far Amie was carried down into the gully.

Slabs usually occur when wind transports new snow from the windward side of the mountain, to the leeward slope. But this creates the perfect cornice, a deadly attraction to the mountains. It’s weak and can break off easily, forming its own avalanche as it goes.

They occur through turbulent suspension of snow in the air and through saltation along the surface of the snow. These processes break snow into smaller pieces before they get deposited on the leeward slope, becoming a dense cohesive layer of snow.

Skiers in the back country are always pushing boundaries and aim to go further, faster and higher than anyone else. But Blair says that “in most cases, the higher up you go, the more hazardous it gets” for an avalanche to occur. The aspect, which affects how wind deposits on a slope, the intensity of sunshine on snow and the density of old snow are other factors that, along with the altitude, influence an avalanche.

However, these factors can easily be forgotten about when you are wrapped up in a perfect powder day. Amie remembers “We didn’t think about the avy (avalanche) report that we all read, we didn’t think about the aspect, we didn’t think about the elevation, we didn’t think about the fact it was low. We just blindly did what we thought we wanted to do.”

Blair explains that “wind is one of the predominant factors. Generally the stronger the wind, the more it breaks up the snowflakes into small rounded particles and packs them together. The stronger the wind, the denser the packing and the harder and stronger the layer of snow that is deposited becomes.” These layers are called wind slab.

The greatest avalanche hazard comes when layers of snow get laid down over the top of a softer weaker layer snow. When chasing good snow or the perfect powder run, it’s easy to be blinded by the fact that this snow could be lying on top of an unstable layer. An avalanche doesn’t know or care that you are an expert; the snow quickly becomes your enemy, as John Stifter found out.

He was involved in the avalanche at Stevens Pass, Washington, in February 2012 that took the lives of three very highly experienced skiers. After losing two friends in the accident, he vowed he would never ski again.

“It’s like, how can something that you love so much, become so evil? I just didn’t trust it; I didn’t trust any of the slopes, any of the snow that was underneath me, even in bounds” he said.

Each layer of snow is reflective of the meteorological conditions in which that snow fell. The snow then continues to change over the influence of the conditions that continue.

The three main reasons why and how your favourite backcountry spot might, or has, collapsed on you, are explained here. The three weakest layers that occur beneath your skis:

The risk of being caught in an avalanche changes every day, with multiple factors to take into account. But it’s clear speaking to experts in the field and those that have unfortunately experienced these incidents, that education is key. Blair recommends, “speak to the ski patrollers or people like that who know the area and know the conditions and know what’s suitable and what isn’t”. And while Martin is a self-confessed powder hound, he’s still safety conscious. He says: “Be humble to Mother Nature and train yourself for the worst case scenario; always hope for the best. But the most important thing? Have the knowledge and respect for the mountains.”

John and Amie are two extremely experienced skiers who have grown up in alpine settings with powder at their doorsteps. Their stories both illustrate that snow is a most unpredictable force that can change your outlook on skiing and life in an instant. While it took John a whole year to get back on skis and what he witnessed means the backcountry is an almost forbidden zone, Amie was clipping back in after a week. She isn’t put off. For her, “It’s part of life. There’s risks; I’m not going to stop driving my car because I could get in a car accident.”